|

Spring 2006 Courier Voyage of Deception:

|

|

| Moses Myers was the Dutch Vice Consul in Norfolk. His letters to the Dutch Minister in Washington provide insight into the Louisa affair. |

Would Myers, in his capacity as Dutch Vice Consul for Virginia, find out why? As Myers wrote to the Dutch Minister to the U.S., the schooner was libeled “for having contravened both the United States and [Virginia] laws the captain having brought into this port sundry Negroes & sold them in a clandestine manner.” An examination of various admiralty court documents, Myers’ consular correspondence and newspaper accounts reveals a story of deception and rapacity on the part of the schooner’s master Christoffel Rasmyne.

The vessel had departed from her homeport on the Dutch island of Curacao

in May bound for a port in the United States. Among her crew were four

“free men of color”— John Joseph, Peter Martin, John

Lewis and John Rose. The first three were seamen and the last a cook.

Unlike most 19th Century occupations, that of merchant seaman was one

of relative equality. Each of the four was paid a monthly wage ($10

in the

case of the sailors and $7 for the cook) that was identical to that

paid to white members of the crew.

|

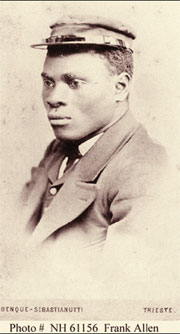

| Norfolk-born Frank Allen had already been to sea before joining the U. S. Navy in 1867. The occupation of merchant seaman was one of the few offering wage equality for Blacks in the 19th Century. |

Bad weather intervened and the schooner’s foremast and flying

jib

boom were damaged. Mr. King, the vessel’s owner, conferred with

Captain Rasmyne and decided to make for Norfolk where the cargo was

landed. A day or two after the schooner’s arrival on June 22,

1817, all of the white crew members except Captain Rasmyne and Peter

Lindquist asked to be discharged and were paid off. Captain Robert Threlfell,

master of the British bark Alknomack visited on board the Louisa.

He warned both King and Captain Rasmyne that the black crewmen should

remain aboard on the schooner. Despite their being free men, if they

went onshore without the necessary papers, they were liable under Virginia’s

laws to be taken up and sold into slavery. Mr. Kings’ response

was immediately to caution the four blacks of the possible consequences.

Captain Rasmyne apparently came up with another idea.

|

| The above legal notice ran in the Norfolk Herald for three weeks in 1818. |

A few nights later, two of the previously discharged crewmen came aboard to collect their gear. After sharing drinks with John Rose, they apparently convinced him to go ashore with them. When King was informed of Rose’s absence the next morning he was “very much vexed” and cursed the sailor on watch for letting him go. By the next morning the remaining black crewmen had disappeared from onboard. From depositions in the case it was apparent that they had been alone on the ship except for Captain Rasmyne. Further investigation revealed a smoking gun. Port officials came up with a bill of sale signed by Captain Rasmyne selling the four men to John Ott and George Sargent of Norfolk. Ott and Sargent in turn clandestinely carried the sailors to North Carolina where they were offered for sale. The suspicious circumstances caused the blacks to be taken by municipal authorities who then used local ordinances to sell them into slavery with the proceeds going to the authorities. By the time this was discovered, Captain Rasmyne had fled Norfolk aboard an outbound ship. One person who knew him described Rasmyne as “an ignorant man” who had been raised from before the mast by Mr. King.

Ignorant or not, Rasmyne displayed loyalty to neither his owner nor his crew. The trial before Judge St George Tucker was delayed until the November term of 1818. By the time the case was heard, Joseph King had run out of money despite Moses Myers’ efforts to help him and had left town. Although no judgment was made against King personally, the ship, its equipment and cargo were forfeited to the U.S. government and sold at auction for $695. There is no evidence available to explain what happened to Joseph, Martin, Lewis and Rose.

You Are Here: Home > Essays and Artifacts > Insights from The Courier > Spring 2006 > Voyage of Deception: Captain Rasmyne and the schooner Louisa www.NorfolkHistorical.org |